(The Immigrant Heritage Hall of Fame would like to thank Kamila Herzog and her granddaughter, Cassandra Skobrak, for their assistance in preparing the following story about 2017 IHHF Inductee Franciszek “Frank” Herzog.)

Franciszek Herzog unfortunately did not live long enough to appreciate the honor of being inducted into the Immigrant Heritage Hall of Fame, but his life was never about recognition; he lived to help people, especially children.

Franek was born in Poland, the third son in a military family, and lived there until World War II. His father, also Franciszek and a Lieutenant Colonel in the Polish Army, was engaged in the war from the very beginning. Unfortunately, the Polish Army had to capitulate, at which time his father was captured by the Russians and taken to a POW camp with about 4,000 other officers. It was later discovered that there were three camps, and altogether about 15,000 officers, policemen and other government employees were murdered there in what became known as the Katyn Massacre.

Meanwhile, Franek, his mother, and his elder brothers Waclaw and Tadeusz were deported to Siberia. His mother died there due to a shortage of food and medication, leaving the boys orphaned.

After their mother's passing, the Herzog brothers learned that a Polish army was being formed in Southern Russia, along with Polish orphanages. The three brothers managed to make their way to Tashkent, in Southern Kazakhstan, where Waclaw joined the Navy. Tadeusz, 15 at the time, and Franek, 11, were taken into the orphanage and evacuated to India. The conditions of the camp were spartan; Americans would consider these conditions deplorable, but after what the Herzogs had been through it seemed liked heaven. Franek’s reminiscences of life in India were always fond ones, and it was during this time that he discovered Polish Scouting, which would become a lifelong passion.

In 1947, Franek was able to join his brothers in England, but he was unsure what to do next. Being 16, he had few choices for work. Fortunately, fate led him to a scouting instructor from India who helped him gain acceptance to a Polish High School, which was formed especially for displaced people. He finished high school and prepared to take English exams which would allow him to go to college.

The prospect of attending college was anything but simple; although education was free, he still needed somewhere to live and the ability to support himself. A grant gave him enough for the two years of college, and he secured lodging in a very small and basic room. After the war, in London, housing was very difficult to find; some parts were in ruins and a lot of food was still rationed. Franek managed to survive, though, grateful for what he had. After college, he began working as an electrical draftsman while continuing his education by taking evening classes. It was about this time that he met Kamila Mikucka and they were married in 1956. Their daughter, Ivona, was born in 1959, and they remained in London until 1962.

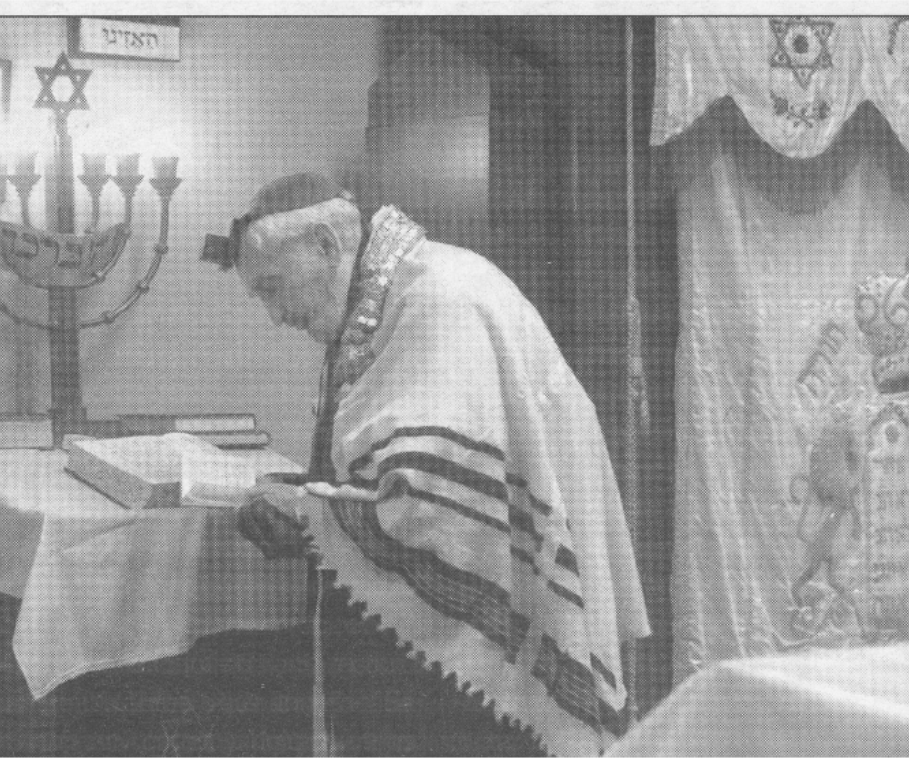

Franek’s involvement in Polish Scouting continued. In addition to managing his family, work and studies, he always found time for the scouts, attending weekly meetings with his troop and helping to run summer camps.

In 1962, after seeing an advertisement for a position with Northeast Utilities in Connecticut, Franek and his wife decided that they were ready for a new adventure. Franek submitted his resume, got an interview in London, and was offered a job as an electrical engineer. In a few months, the family moved to Connecticut. Shortly after, while attending the Pulaski Parade in Hartford, they were surprised to see a group of Polish Scouts marching in the parade. Franek instantly made some connections with the scouts, and a few months later started helping.

In 1974, Franek learned of a site in Palmer, Massachusetts, which would be perfect as a camp for the younger children. He made arrangements, recruited some help, and began running an annual two-week summer camp which continues to this day. Each year the group grew larger and with it, the demand for more help. Not many people volunteered to use a week or two of their vacation time working with the scouts, but for 37 years Franek organized the camp and did much of the work on his own. He always believed that scouting, no matter the nationality, was valuable in building character and solid citizens.

He also firmly believed that people should always know their roots, and was dedicated to learning all he could about his own. After discovering that his father and uncle were executed in a POW camp in Russia, it was Franek’s own extensive research that determined they were killed in the Katyn Massacre, a series of mass executions of Polish nationals conducted by Soviets. Although the mass graves were discovered in 1943, cover-ups refusing to implicate Russia stayed in place until 1952. At that time, the United States remained silent on the matter. Franek was unrelenting in his efforts to gain acknowledgement and an apology from the United States for its role in keeping word of Russian involvement suppressed.

For all his devotion to Poland, Franek was a fine American, happy in his adopted country. He was deeply proud of his family: his wife, Kamila, was always supportive in any way she could be and is a model of diligence, notably making their home in Hebron into a veritable Eden. His daughter Ivona is the wife of a Naval officer who worked his way up through the ranks after enlisting, serving his country for 39 years before retiring with the rank of Captain. Though this meant picking up and moving every few years to such places as Scotland, Hawaii and Guam, they embraced the chances to experience so many different surroundings and cultures. Two of his grandchildren also chose military routes. The oldest, Stephen, joined the Marines, doing two tours in Iraq as well as two years stationed in Okinawa. The youngest, Greg, also joined the Marines, going through Officer Candidate School, and is currently waiting to see what life will have in store for him. The middle grandchild, Cassie, recently completed her Master's degree in Library and Information Science. They are all exemplary citizens who learned much about Poland, Polish customs and life from their grandfather, whom they loved and respected.

Because of his background as an orphan, and being helped by so many people and organizations along the way to build character and become a good and productive citizen, Franek felt his duty was to give back and do the same for others in whatever ways he could. Together with his friends, he organized help for poor families in Eastern Poland, Belarus and Ukraine. He also organized help to Polish Scouting in Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania. Helping others was always his focus, throughout his entire life.

Ann Horelik,, who was brought on by Franek in 1974 to help run his scout camp in Palmer, remembers Franek fondly.

“Frank loved children, and he loved everything to do with scouting,” she says. “He was a very caring, very loving man. He demanded respect, he got it, and the children loved him.

“I think because of his experience, having been an orphan himself, he understood how much children needed love, nurturing and guidance. And he devoted his life to providing it.”